In the early 1970s, synthesizer development took a U-turn. The focus went from enormous metal hulks to portable form factors, many of which folded up into nifty little cases. The way manufacturers executed these designs varied wildly. Some looked like a smaller version of a suitcase Rhodes piano, basically a synth with a wooden top cover. Others were expertly disguised into briefcases unfolding into downright clandestine-looking mystery machines. With some research and a little expert insight, we’re going to investigate how this phenomenon of hyper-portability came about and then go through the most interesting units one by one.

Big Beginnings

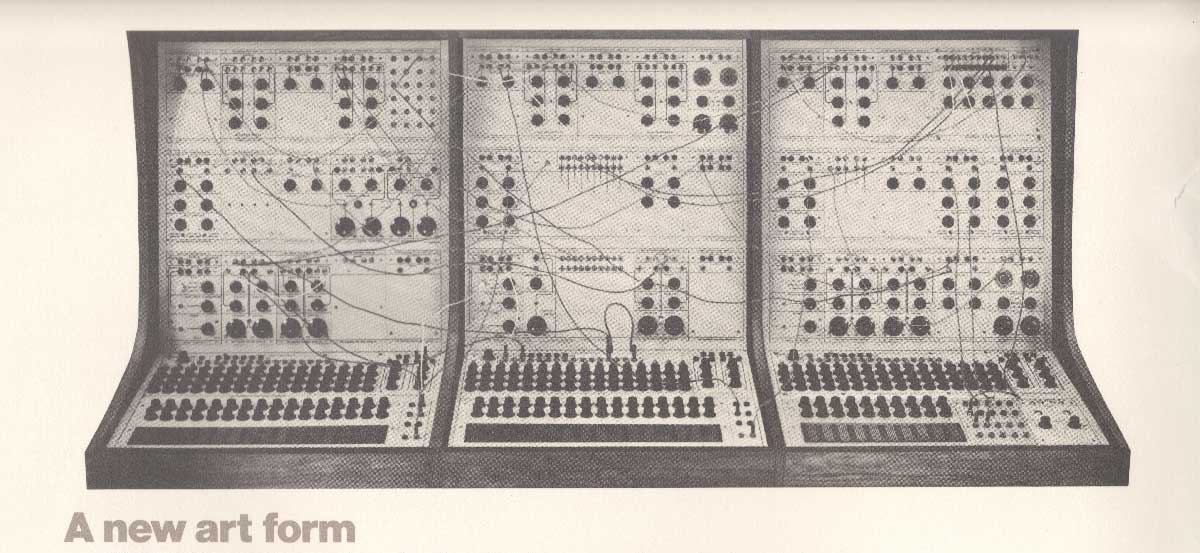

The first commercial synthesizers were imposing machines: the earliest modular systems were usually comprised of one or more towering wood-encased monoliths. Most of the customers of these early units were well-resourced entities, often big-time composers or universities with specific needs. Manufacturers met these varying needs by employing easily customizable, fully modular designs.

Initially, there was no rule book on essential synthesizer modules or strong conventions for signal flow. Many of these early units swelled with an excessive number of modules. Some Moog modular synthesizers had as many as ten oscillators, and early Buchla 100 systems might have space for thirty or more modules. Things could get out of hand quickly, both financially and spatially.

While these expensive giant synths weren’t an issue for the first waves of wealthy customers, they could never work for the masses. As time went on and synthesizer design developed more universal guidelines, it was inevitable that manufacturers would seek more practically sized instruments if they intended to grow the market. Synthesizer expert, Tom Rhea, elaborates:

“It's no mystery why manufacturers of analog synths developed 'suitcase'... formats:1) They were cheaper than modular systems; 2) by that time, everybody had figured out the minimum "modular" necessities (VCO/VCF/VCA with envelope generators and perhaps an LFO); 3) by that time, pop musicians had discovered analog synthesis and wanted something they could take on the road!”

- Tom Rhea, PhD., Former Moog Clinician, Author, and Electronic Music Educator

The Move to Semi-Modular

It was clear that synthesizers had to get smaller, but that wasn’t the only design issue: using modular synthesizers was hard to learn with the few educational resources that were available.

With a fully modular synthesizer, you don’t get any sound until you wire a patch with the correct signal flow. This means no immediacy, a tougher learning curve, and an overall bigger barrier for beginnings to navigate. It was also less than ideal for the stage.

On the other hand, removing modular functionality also meant losing a lot of sonic possibilities, perhaps the reason why some of the passionate creators of early synthesizers were hesitant to build more limited portable units (including Bob Moog himself). However, the need for more accessibility was overwhelming, and, luckily, manufacturers came up with a brilliant middle ground: semi-modular synthesizers.

In a semi-modular synthesizer, the connections between modules are hardwired or “normalled” in a conventional signal path, meaning you could press a key and start getting sounds right out of the box. But the connections also have optional patch points that you could wire with patch cables, allowing you to modify signal flow and experience the benefits of modular synthesizers in a more user-friendly device. Most portable or suitcase synthesizers used either semi-modular systems or the standard hardwired designs that have become the norm today.

“Semi-modular seemed to be one good option—patchable, but not movable/changeable modules. [It] Streamlines the workflow not to have to patch everything up each time! So besides the portability, it was faster to operate than fully modular—but not nearly as powerful.”

- Brian Kehew

These changes dramatically improved the ability to get synths into the hands of more people and to be used for more applications. Let’s dig into some of the models that made it happen.

EML ElectroComp 200

Leading the charge towards portability, Connecticut manufacturer Electronic Music Laboratories (EML) released one of their first synthesizers, the ElectroComp 200, in 1969. It was monophonic, fully modular, and had no keyboard.

Some interesting features include a waveshaper, dual ring mods, and spring reverb. The ElectroCom 200 was best used as an educational unit or when being supported by other ElectroComp gear. The EML 200 was often paired with paired with the EML 300 controller. The 300 had its own VCO, envelope generator, and VCA, as well as a note trigger controlled with a telephone-style number pad rather than a keyboard.

EML ElectroComp 100 & 101

EML released the duophonic Electrocomp 100 in 1970, which was replaced by the very similar 101 model in 1972. It traveled as a neat wooden box that came apart and reassembled into an upright panel accompanied by a 44-note keyboard.

The ElectroComp 101 delivered quite a few unique features for the time. Starting with its four oscillators: firstly, they used op-amps instead of transistors, which made for more temperature-stable tuning. They were also continuously variable wave shape oscillators, meaning not only could they achieve sine, square, and pulse waveshapes but also everything in between. There was also a multi-mode filter, two envelope generators, and a sample and hold module. The cherry on top is both the ElectroComp 100 and 101 were semi-modular with no distinction between audio and voltage; any output could patch into any input.

The ElectroComps had a big, powerful sound that found its way into the works of many artists, including Foreigner, Skinny Puppy, and Weezer—and quite famously, EML synthesizers were used by Allen Ravenstine and Robert Wheeler, each synthesists associated with early avant-rock group Pere Ubu.

ARP 2600

The ARP 2600 is easily the most famous synth on this list. The ARP 2600 descended from the massive ARP 2500 modular synthesizer. While ARP couldn’t possibly pack the 2500’s full feature set into the 2600’s suitcase design, its semi-modular design still maintained an enormous amount of functionality and versatility. It expertly ranged all the sonic landscapes expected of a world-class synthesizer: creamy leads, big basses, etc. But the ARP 2600 also broke more novel ground with less conventional sonic applications; it acted as a wild effects processor for Pete Townshend’s guitar and as the voice of beloved Star Wars astrobot, R2-D2.

Created by an aviation interface designer, the ARP 2600 panel carries the characteristic looks of a serious and consequential machine. As with most manufacturers of the time, educational facilities were a big target for ARP, so the layout and labeling were practical and intuitive. Rather than knobs, most controls used faders, which remains fairly unique to this day. The faders allowed the player to quickly asses the settings with a glance, as it’s much easier to see where faders are set than small knobs.

Particularly notable modules include an external input with a powerful preamp (used to drive Townshed’s heavily ARP 2600 affected guitar), stereo spring reverb, and an envelope follower. The envelope follower was a big part of how Star Wars sound designer Ben Burtt gave R2-D2 his organic charm. Along with employing the ARP’s capacity for futuristic bleeps and bloops, Burtt modulated parameters using his voice via the envelope follower. In addition to layering the synth output with actual vocalizations, this brought R2-D2 to life as one of the world's first lovable robots.

There’s a lot more to say about the ARP 2600. Check out Ryan Gaston’s walkthrough to explore the 2600 a little deeper.

Moog Sonic Six

Moog’s contribution to suitcase synths delivered what was arguably the most seamless case design. A lot of the synths on this list were built with two halves that come apart and then reassembled into a playable form. Not the Sonic Six; its gigging-appropriate flight case opened gracefully with a 49-note keyboard and upright panel immediately ready for use–it’s a clean look.

The Sonic Six started as the Sonic V, which was designed by an ex-Moog employee for a different company: Musonics. Musonics ended up purchasing Moog two years later, after which the Sonic V was improved and released as the Sonic Six under the Moog Music Inc. name in 1972. The most significant differences between the Sonic V and Sonic Six were the flight case used to house the Sonic Six and the use of a Moog ladder filter in the Sonic Six.

The Sonic Six is duophonic, with two oscillators capable of saw, triangle, and square. While it had variable pulse width, you couldn’t modulate the pulse width. This is a good time to point out that, unlike many suitcase synths, the Sonic Six wasn’t semi-modular, though it had some interesting built-in modulation options, largely because of its dual LFOs (labeled “Wave Generators” on the panel) with their individual and mixed rate knobs.

EMS Synthi AKS

The Synthi looks like it stepped onto the stage right out of '60s sci-fi set, with big safe-dial tuning knobs, a wholly unique pin patch bay, colorful controls, a VU meter, and a joystick. Released in 1972, the EMS Synthi AKS was one of the most compact suitcase synthesizers, fitting into a thin plastic case a little larger than a typical briefcase.

The fully modular Synthi had a unique patching method, using battleship-style pins in a matrix to make connections. The Synthi was a mono synth with three oscillators, one of which could dip into subsonic territory for use as an LFO. It had a low pass filter, trapezoid envelope generator, ring mod, dual spring reverb, noise generator, dual input amps, a joy stick controller, along with 30 touch capacitive “keys” for control. The routing flexibility made the Synthi good for truly unique sounds.

[Above: an excellent video of musician Alka exploring the EMS Synthi AKS]

The Synth AKS was preceded by the VCS3 (1969), which was a very similar unit minus the plastic briefcase housing. Its wooden housing and much larger form made it less than ideal for gigging. In 1970 the Synthi A was released, which is identical to the Synthi AKS, minus the touch capacitive keyboard/sequencer. EMS also later released the Synthi E, a model designed for educators; it even had a whole curriculum built around it. The Synthi E used CV patch cables instead of the pin matrix. It had the basic elements and a little more but was missing certain charms, such as the spring reverb.

Many electronic composers have used EMS Synthi instruments in their work, ranging from Jean Michael Jarre to Aphex Twin. The Erica Synths Syntryx II is a modern synth, generally considered to be a spiritual successor to the beloved Synthi.

Buchla Music Easel

The Music Easel is essentially two modules from the Buchla 200 Series: the 208 (stored program sound source) and the 218 (touch plate keyboard). This extremely rare synthesizer was built into an aluminum briefcase. The Buchla 200 series introduced some seriously wild and truly revolutionary synthesis concepts—and the Easel is one of the best-encapsulated examples its power.

[Above: filmmaker Alex Tyson's popular video of Music Easel virtuoso Charles Cohen.]

A prototypical design of what is now often referred to as “West Coast Synthesis,” the Easel did things other synths simply could not. Its complex oscillator could be modulated to not only morph between preset wave shapes—but could also modulate between varying stages of complexity via the Timbre control (implemented in later versions of the instrument using a wavefolder). It employed a dual low pass gate that could attenuate spectrum and amplitude at the same time, imparting a unique acoustic-like character onto its sound. Its touch plate keyboard featured 32 pressure-sensitive keys. Bringing it all together, the Easel's 25 patch points, five-stage sequencer, complex random voltage generator, envelope generator, and pulser provided a lot of modulation possibilities. And frankly, that's not the half of it—the Music Easel is a profoundly deep instrument.

The design of the Buchla Music Easel and other Buchla instruments was focused on forging a path into composing electronic music as its own thing. It wasn’t about crafting the likeness of something acoustic or “real” but more for new sounds and new methods of writing music.

The modern-day company Buchla USA produces a several modern takes on the Music Easel, adapted by their staff to add new features and quality-of-life improvements like MIDI implementation, extended patching options, and more. They're not quite the same as the original 1970s Music Easel, but many modern musicians find that they provide a great sense of Buchla's unique musical philosophy.

Oberheim TSV-1 (Two-Voice)

The legendary Tom Oberheim’s first products were effects, sequencers, and other supportive products for other synthesizers, one of which was the SEM (1974). The SEM was a complete synthesizer with two VCOs, but it was designed more to support other products, including Oberheim’s successful sequencer and ARP and Moog synthesizers. It wasn’t long before two SEMs were combined with a sequencer and a 44-note keybed to create the Oberheim TS-1 “Two Voice.” The Two Voice was a creamy-sounding duophonic synthesizer with some neat tricks. One of which was the ability to play over the sequencer; the sequencer could be set to control only one of the voices, leaving the other open for the player.

Each SEM in the Two Voice had two VCOs, a multi-mode filter, two envelope generators, and an LFO. However, since the SEMs that made up each voice were discrete, they had to be individually set, something that some users expressed frustration with. The problem was compounded in the Four Voice and Eight Voice Oberheims that employed the same SEM bundling concept.

Like the Buchla, the Two Voice got a recent reissue: the Oberheim Two Voice Pro. It makes sense, as even the vintage Two Voice still manages to find its way into modern works, like the score to The Life Aquatic and the opening theme for Stranger Things.

Where are All the Suitcase Synthesizers?

After the '70s, the suitcase form factor didn’t heavily prevail, but the design shifts they introduced certainly did. The mix of portability and streamlined functionality became the norm. Sure, these synthesizers couldn’t do everything their massive and expensive predecessors could, but they didn’t need to. Performers, composers, and sound designers got by exceedingly well with these more limited but practical designs.

Would Ben Burtt have been able to commission a giant ARP 2500 had the 2600 not existed? These suitcase designs, if not fully responsible for the rapid adoption of synthesizers, at the very least, accelerated it by light years.

The era of the suitcase synthesizer marked the end of the world’s introduction to synthesizers. The initial oohs and ahhs were over. It was time to get to business and start enjoying these wondrous machines on a bigger scale. And once people got used to the idea of synthesizers as practical gigging machines, there was no going back.