I love the name “Mutable Instruments”: it brings to mind thoughts of transformation, progression, the idea of a continually evolving idea. It’s an apt title that describes not only the ever-shifting sounds and functions which came to define this company, but of their instruments themselves. In stark contrast to the industries of music gear and tech writ large, Mutable Instruments’ source code is readily available for anyone to replicate, build upon, or just to tinker with and admire as an impressive piece of construction. Indeed, the open-source nature of Mutable Instruments' work has provided a common point of reference for many new instrument designers as well: studying Mutable's schematics is a masterclass in digital and analog design for musical instruments.

Of course, providing a clear window to the inner workings of your product might be an alarming thought to most people in the world of commerce. The success of a company is predicated on the idea that its intellectual property is novel—that it creates something which no one else can replicate. Whether you’re talking about copyrights or trademarks, patents, circuit boards, or Batman, the pesky thought of legally owning a thought is sewn into modernity.

But maybe it’s a matter of perspective.

For company founder and all-around awesome person Émilie Gilllet, the idea of a closely-guarded trade secret amounted to hoarding knowledge. In her own words, “It's part of my scientific / academic background in which sharing is a habit. It's because I'm really appalled by the way some hardware or plug-in companies make people believe there's a ‘magic ingredient’ in their product: being transparent about how your product works is a remedy against that.”

In stark contrast to many other operators in music tech, Gillet placed an open source ethos at the core of her company, and by doing so, made Mutable Instruments one of the most celebrated and consequential names in modular synthesis of the past 15 years. The shifting sounds of Rings, the dreamy textures of Clouds, the dizzying sonic arsenal of Plaits—all of these names at one time sounded like descriptors on an Etsy listing, but now are legendary names in modular. To this day on ModularGrid, the Plaits, Rings, Clouds, Beads, and Marbles modules rank among the top twenty most popular Eurorack modules altogether.

Legions of devoted fans continue to include MI modules in their setups (myself included), and have waxed poetic on their wonder ad nauseam in forums. Simultaneously, enterprising coders have iterated, improved, and reproduced MI modules until they actually became an industry unto themselves of hot-rodded clones that comprise the majority of the portfolios of the companies making them.

Even in the afterlife, Mutable Instruments continues to exert a planetary gravity in modular. In April 2022, Émilie Gillet announced that no new modules would be produced, no further inventory would be made, and by the end of that year, the company would close its doors. That was it. In the words of Gillet, “There is no easter egg, no plot twist, no teaser.”

For a company that in part built its name on the mind-bending depth of its modules and all the hidden sonic treasures to find, it kind of felt like a magician emptying out her bag of tricks, brushing off her hands, and walking off stage. Could it really be over like that? It could and it is, but no new production doesn’t mean MI has vanished. Far from it.

Thanks to the ingenuity of her designs, we no longer expect a filter to just offer a frequency sweep or an oscillator to just give you a sine, a saw, and a square as in the days of Doepfer (still love you, Doepfer). Gillet’s inventions drastically changed how we think of what a module can and should do, so today, let’s look at three points: how Mutable Instruments came to be, how they pursued and developed distinct themes throughout multiple modules, and how even though they’ve been shut down for years, you won’t have any problem getting your hands on a Mutable Instruments module.

DIY Beginnings

Prior to thinking up modules that could sound like melting bells or robots trying to have conversations, Gillet was approaching music in a different way for entirely different people. She previously worked for companies like Google and Last.fm where she worked in research for machine learning and signal processing, specifically in analyzing songs to yield information like BPM or genre. It wasn’t until 2009 that she began experimenting with Arduino boards, an open-source electronics system popular in the DIY community.

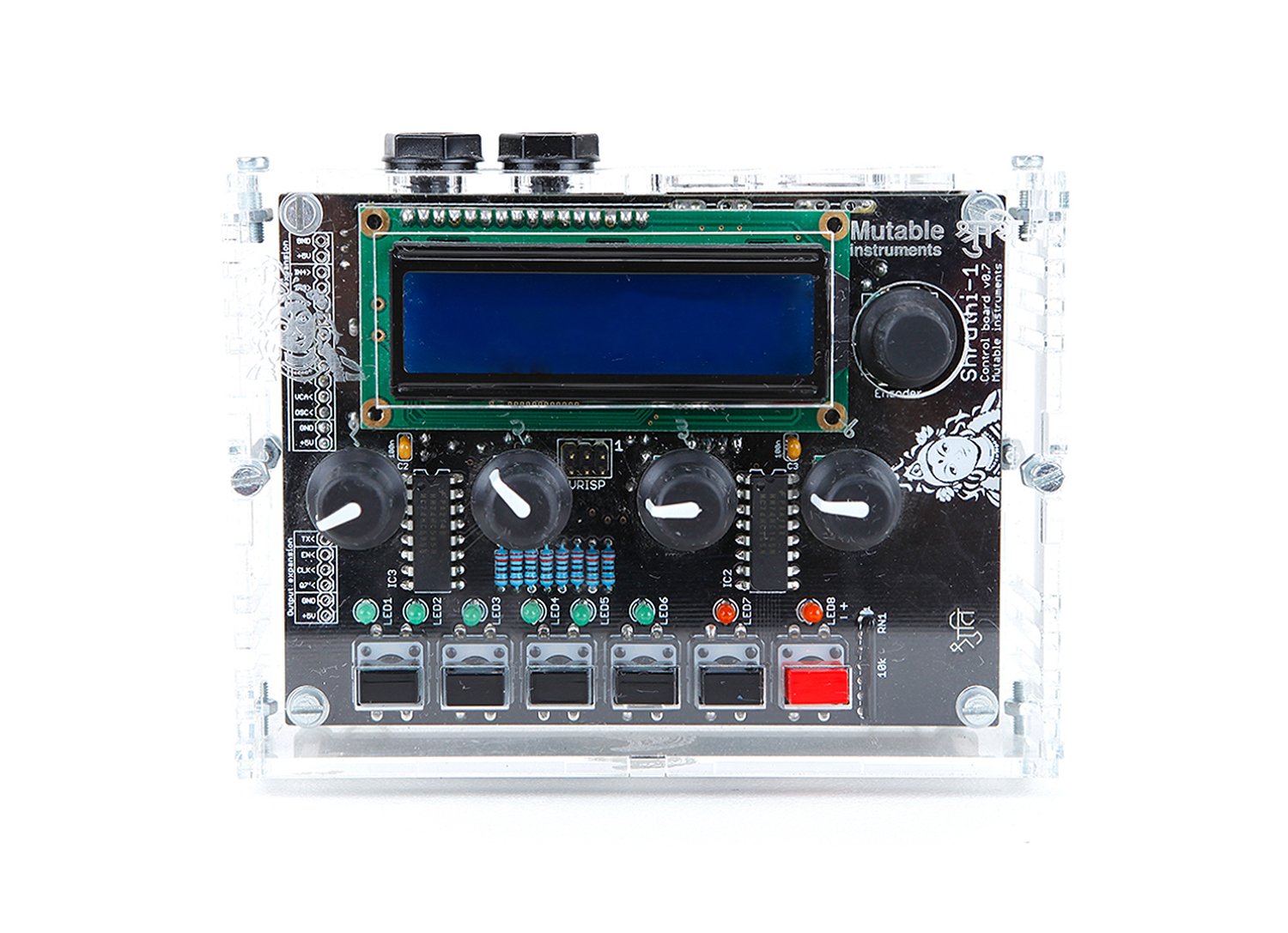

From her time spent working on these boards, the first Mutable Instrument took shape in the form of the Shruthi-1. Bearing more resemblance to a wall-mounted thermostat than the sleek modules that came to define MI, the Shruthi-1 was a boxy, compact monophonic digital sound source paired with an analog mixer, VCF, and VCA. In spite of its modest appearance, this little synth demonstrated the considered design and crazy amount of functionality in a small footprint that became calling cards of the company.

The tiny titan comprised two halves: a digital circuit board which handled sound sources, mixing and EQ’ing, LFOs, envelopes, and a 16-step sequencer and arpeggiator. The other half was made up of a second circuit board, this one analog, and it offered a voltage-controlled filter and amplifier as well as the option to process external audio (another Swiss-blade feature found in many MI modules).

While today we expect a wide palette of waveforms with tailored parameters, the Shruthi-1 delighted many synth devotees of the time with its versatile sonic offerings. Across an 11-octave range, users could shape and animate their waveforms, ranging from a sine or a saw to more eye-catching offerings like onboard wavetables, two-operator FM synthesis, and even some simple formant synthesis with 14 vowels and two consonants. Gillet even included a duophonic mode in firmware updates, a prime example of the open-source ethos at work towards an improved, fun-infused product.

Paired with effects like grungy bitcrushing and phase distortion, a meaty filter, and a modulation matrix with 12 available slots, the Shruthi was a marvel of its time, designed to be powerful and profoundly affordable. The synth quickly developed a cult following—and its users had a voracious appetite for more instruments. Gillet began to turn more of her attention to Mutable Instruments, handling the sourcing and shipping of kits as well as iterating on firmware and introducing updates in correspondence with the community over forum posts.

The Shruthi was followed in short order by the polyphonic Ambika, which offered a six-voice design with two oscillators and sub-oscillator per voice, and new features like multiple filter modes. With her second synth in production, Gillet started planning her most ambitious project yet, a flagship version of the Ambika. In 2012, she bought a Doepfer system with utilities like LFOs and a clock source for testing. She quickly took to the Eurorack modular format, and concurrently found an influx of devoted fans asking for a module version of the Shruthi.

Enter the Anushri, released in 2012. This dual monophonic synth/lo-fi drum synth, though developed largely for standalone use, featured an array of control voltage I/O. It was commonly adapted for use in Eurorack systems, as well—making it Mutable Instruments’ earliest formal entry into the world of modular. Working from previous playbooks, the Anushri featured two digital sound sources paired once again with an analog mixer, amplifier, and filter. The largest step forward was the inclusion of a patch bay to noodle with CV parameters like oscillator frequency and filter cutoff, as well as nifty additions such as Ins/Outs for Gate and Clock.

Gillet’s talent for layered functionality also came into fuller focus with the Anushri. The button section allowed users to cycle through synth and drum pages, sequencer functions, and recording, but the Hold button revealed deeper mysteries to initiates willing to read the manual. When certain buttons were pressed while holding Hold, features like simultaneous modulation of the VCO or VCF with envelope and LFO and manual drum triggering emerged from the synth’s depths like pulling on a candelabra and revealing a secret door in the wall.

Worth noting: some modular iterations of Anushri use the now-iconic MI aluminum faceplate, grayscale graphics, and much-beloved teal and magenta knob colors and panel highlights. The brand iconography came from a partnership with Papernoise Design, a graphic art studio based near Trento in northern Italy who has also worked with the likes of Alright Devices and Hexinverter, among others.

So, with a design ethos in place and several successful instruments out in the world, Mutable Instruments went wholeheartedly into modular synthesis. In 2013, the first true MI module came to the market and pushed the company to new levels of fervor and fandom: the iconic Braids.

Evolution Through Iteration

Mutable Instruments no doubt produced many of the most influential electronic musical instruments of our time; but let's take a look at some of our favorites. In particular, we'd like to highlight some specific instruments that showcase Gillet's tendency to refine her ideas over time—showing her brilliant iterative approaches to instrument design.

The Forebear: Braids

When you call something a “Macro Oscillator”, you had better be able to back it up. The Braids wove together an (for the time) eye-catching 45 separate synth modes that ranged from monster CS80-style saws and toothy wave folding to Karplus-Strong physical modeling, expansive wavetables, and even rudimentary granular synthesis—a sign of new horizons to come.

Composed of a multi-character, multi-segment LED display, rotary encoder, six knobs and six jacks, Braids packed a wild amount of power into 16HP—acting as an uncommonly intuitive and powerful sound source. This maximalist approach to what an oscillator can offer left reverberations throughout Gillet’s approach to new modules and through the world of modular design writ large. For many newcomers (myself included), Braids offered enormous value and an inviting interface that stood in contrast to more involved modules that seemed difficult to operate.

Again, Gillet’s knack for considered design shone through here. The decision to provide only two controls for Timbre and Color, the former usually controlling brightness and the latter a mode-specific parameter, made intimidating concepts like VOSIM or formant synthesis accessible and fun to explore. In spite of the fact that the module was released over 10 years ago, it is still readily available thanks to the open-source concept from third-party developers like Tall Dog Electronics.

While the Shruthi and its brethren predate Braids, Mutable Instruments found its stride in this action-packed module, even if Gillet wasn’t all that enthused by its posterity. “Braids is not my favorite module,” she said plainly and emphatically in a 2017 interview with Clockface Modular. The array of options was in place, but Braids still required its user to do a fair bit of menu diving to navigate the full functionality of the module. When asked specifically about how to best address module complexity, Gillet detailed a set of guidelines she uses during the design phase. In her own words:

- Under any circumstance, the label printed on the panel should match the knob's function

- The module should try to infer as many settings as possible from the way the module is patched, instead of asking the musician to press buttons

- OLED displays and encoders might be OK for something requiring many "set and forget" settings, like a MIDI interface

Hands-On Synthesis: Elements

2014’s introduction of the Mutable Instruments Elements demonstrates these principles in action. Gone were the display screen and compact design, replaced with a solid 34HP slab of knobs and input jacks. This hands-on design consciously engaged the user, keeping you twisting, repatching, and exploring the expanses of modal synthesis—at the time, an approach largely underexplored in the realm of commercial musical instruments.

Modal synthesis is simple at its core: an initial sound called an exciter is sent into a bank of band-pass filters called a resonator. That exciter is amplified or deadened according to its frequencies in relation to the frequencies of the filter bank. The end result is an uncanny approximation of sounds from physical objects, a wide variety of them. Think of how it sounds when blowing on the rim of a glass versus clinking it with a fork. Or hitting a drum with a soft mallet versus a wooden drumstick. Therein lies the magic of modal synthesis.

Elements was divided into two intuitive Exciter and Resonator sections, each with a robust but carefully-selected set of parameters. For example, the Exciter section featured scraping granular noise (Bow), pitched granular noises (Blow), and percussive hits (Strike), with further controls to scan a wavetable of granular waveforms or select from percussive samples or models. On the Resonator side, a Geometry knob altered the resonator's behaviors to simulate different materials and structures, with Brightness emphasizing or muting high frequencies (think glass versus wood). Add in a nifty dab of reverb with the Space knob and you have an engrossing modular experience.

Like Braids, Elements is still in production via third-party builders like the awesome After Later Audio. There are even different layouts in the Quarks and the Atom according to your preferences and space constraints.

Instant Atmosphere: Clouds

In particular, the Resonator and audio processing of Elements captured Émilie’s attention, and over 2014 and 2015, she released two more S+ Tier All-Time modules: Clouds and Rings. We’ll start with Clouds, the famous granular sampl—ahem, I mean “Texture Synthesizer”. The name sometimes confuses newcomers; Clouds is, at its core, a granular audio processor, but it can do so much more than standard granular sample players.

Again championing a sharply-crafted layout with zero fat, the faceplate gives you three distinct sections. The top provides LED reading of everything from your output to audio quality to Blend parameters like stereo spread and reverberation and the ever-fun Freeze to grab and mangle a snippet. The middle provides control over standard parameters like grain start position and size, but includes added functionality like random or ordered grain density and transient smearing. The bottom sported input jacks for all parameters and a mono or stereo out.

Of all Mutable Instruments modules, Clouds received perhaps the most significant instantaneous interest from the modular community, who took to the open-source code with gusto. In addition to Gillet’s own sequel Beads, which streamlined the whole affair, others created expanded firmware and entirely new creations with Clouds as a base. The Monsoon introduced sliders and controls for not only the onboard parameters, but the four Blend controls. Last but not least, the Typhoon rounded up all the souped-up mods under the general banner of “SuperParasites” firmware.

Accessible Sonic Alchemy: Rings

Backtracking a bit, let’s go to 2015 and the release of Rings, one of my all-time favorite, absolute desert island modules. Largely resembling the Resonator section of Elements, Rings also incorporated the LED mode navigation found in Clouds. This nifty addition allowed users to easily select between modes for One-, Two-, and Four-Note Polyphony as well as three Resonator types, creating minimal invasion to an overall organic experience.

Rather than true polyphony, Rings allows up to four notes to overlap one another via short exciter bursts from the Strum input. It comes at the cost of a little harmonics, but the effect is delightful. On the other side, your Resonator types start with the previously-discussed Modal Synthesis model using an exciter and resonator. Sympathetic Strings uses comb filters to simulate unplucked strings vibrating with plucked strings as in sitar playing. Finally, an Extended Karplus Strong (EKS) mode models vibrations through a string via an exciter, comb and absorption filters, and delay modulation.

The beauty of Rings is that it continues to unfold the more time you spend with it, but a beginner could sit down and immediately have fun. The fluid morphing between glass and wood, string and drum, bow and stick is nothing short of enchanting, and Rings deserves every bit of fanfare and third-party reproduction. You can currently score a new derivative of Rings via After Later Audio's Resonate or Tall Dog's uRings SE.

One to Rule Them All: Plaits

Released in 2018, Plaits can be viewed as the unification of all the design principles Gillet cultivated over her career: enormous roster of sounds like Braids, streamlined design like Rings, layers of accessible functionality like Elements, and tailored parameters that give a lot more than you think they will like Clouds.

Clocking in at just 12HP, it became an immediate fan favorite on its release and remains the number one most popular module on ModularGrid. It’s one of the few modules that can do something for systems of every stripe and can captivate you for hours on end with just a sequencer and maybe a quantizer.

In short, it’s joy in a module and the hefty selection of third-party reproductions give you plenty of options, including an itsy-bitsy 6 HP version (it’s cute!).

Thanks for Everything, Émilie

The modules we examined today deserve every word devoted to them, but there are so many more great Mutable Instruments to discover. Peaks is a simple, immensely useful modulation and drum source; Stages boasts an arsenal of function generation to rival the likes of Maths; and Marbles is basically a starter kit for generative patches. We couldn't possibly do justice to Émilie Gillet's entire legacy in a single article, so we'd implore you to search further: her work has an incredible depth, and still offers seemingly endless territory for new musical explorations.

Mutable's designs have been often duplicated in the modular space; but the source code has also been adapted for many standalone instruments, software, and beyond (see the Arturia Microfreak/Minifreak, Poly Effects Beebo, Michigan Synth Works Xena, and others as examples). Gillet's influence is felt through the entire realm of electronic musical instrument design, and countless modern designers owe her a huge debt of gratitude.

I highly encourage you to look over the Mutable Instruments ModularGrid page to find what could very well be your next modular fixation. If you find one that catches your fancy (and I’ll wager you will), remember that for some people, sharing their magic with the world was always the point.