The Korg PS Series of polyphonic synthesizers exists in a strange and unique window of time. They arrived in 1977 amidst a pulsating and frenetic evolution of technology and synthesis. Polyphony was the big subject of exploration, inflating synthesizers to the size of the Yamaha GX-1—but all the while, integrated circuits and miniaturization hinted that this could be possible in something more manageable.

If Korg had started a couple of years earlier, it would have been unfeasible to squeeze that amount of technology into a synthesizer: a couple of years later it would all be largely unnecessary. But at that precise moment, perhaps taking inspiration from a mix of Moog Polymoog, Oberheim 4-Voice SEM, and the ARP 2600, designer Fumio Mieda felt Korg could build something quite extraordinary.

Precursors & Divide-Down Polyphony

There are tiny elements of evolution that you can draw through the Korg product range up until this point, but they are tenuous at best. Korg does like to do things differently. By the start of the 1970s, Mieda had built a prototype for an organ that mixed in a small level of synthesis-style control. It introduced the "Traveler" filter that appeared on a number of later synths, and also gave rise to the KORGUE organ in 1972. They demonstrated Korg's grasp of divide-down, organ-style polyphony that would later form the basis of the PS-Series.

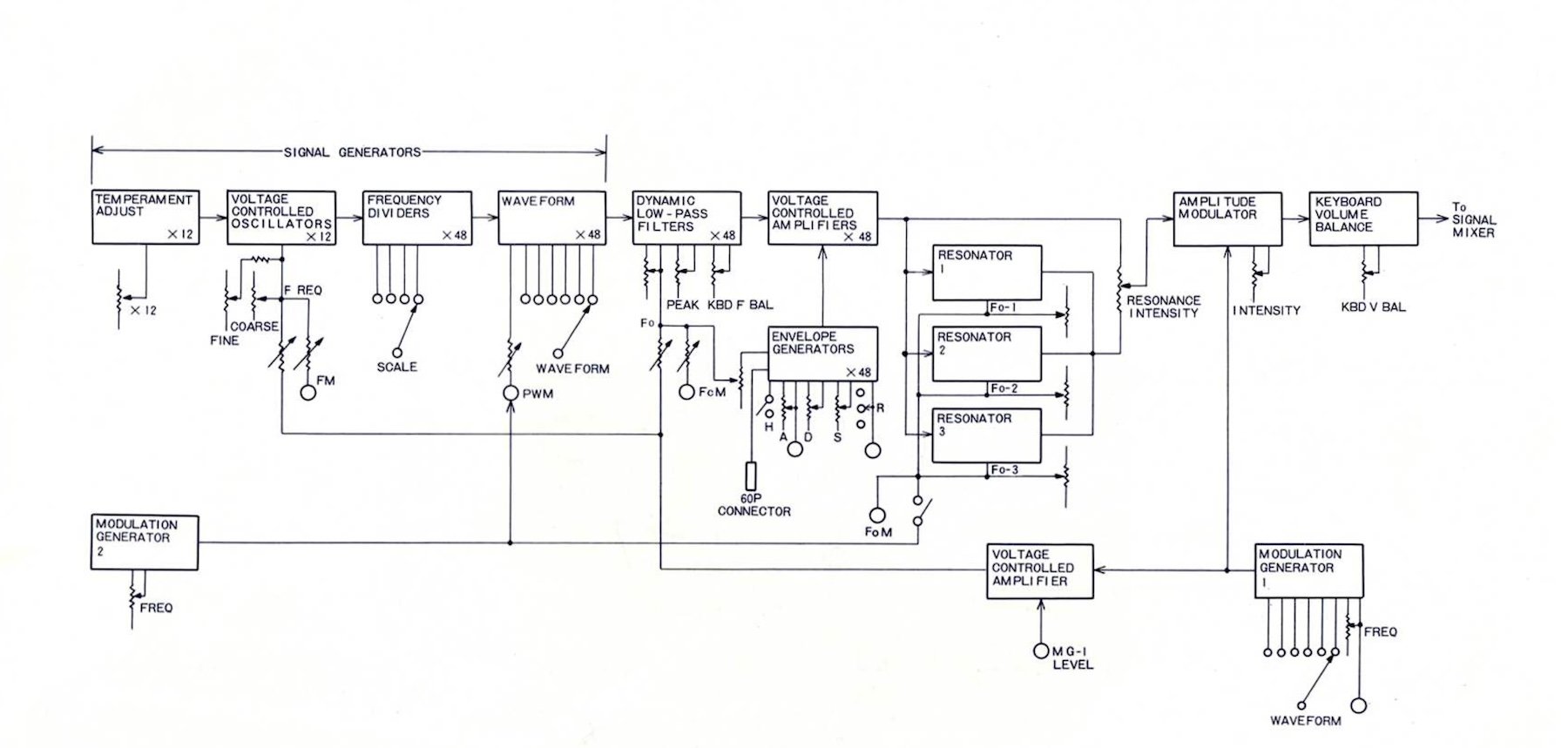

[Above: diagram of the Korg PS-3301 module signal flow, including detail of the divide-down oscillator structure]

The idea behind divide-down polyphony is to have a physical oscillator for each of the 12 notes of the top octave, then split the output and use a clock divider to scale the frequency of the audio down to the lower octaves. This effectively (although not literally) gives every note its own tuned oscillator, resulting in the ability to simultaneously play each note across the keyboard. This is known as "full polyphony", as opposed to limited polyphony, which uses a number of voice cards with variable pitch, all addressable from the same keyboard control data. In this scenario, the number of notes that can sound depends on the number of voice cards—so, for instance, a six-voice synthesizer might have six voice cards (or a smaller number of cards/circuit boards with multiple discrete voices each).

There are arguments for and against both approaches, the main ones being that divide-down can sound weak and static because you are processing an audio signal to get a fixed pitch, whereas with voice cards, the pitch is generated by an oscillator having its frequency controlled by voltage, and so each note comes from the oscillator directly, rather than a derivative process. Ultimately it was the reduced cost, additional programming/sound design flexibility, and convenience of voice cards, and how the majority of musicians were completely happy with the limited polyphony that won out. However, no one seriously accused the divide-down synths like the Polymoog and PS-3300 of ever sounding weak.

[Above: image from the Korg Poly Ensemble user manual]

Anyway, back at Korg HQ, they got distracted into building a few monophonic synthesizers before they had another stab at something polyphonic. In 1976 Korg released the PE1000 and PE2000 Polyphonic Ensemble keyboards. They used a different approach to the KORGUE, where we now have a single oscillator for each note, which is certainly another way of achieving polyphony, albeit a slightly mad one. On the PE1000, despite the full polyphony, the sound was articulated paraphonically through a single Traveler filter and envelope. The PE2000 lost the Traveler filter section, but gained even more oscillators for chorus and detuning effects. Neither was particularly successful, maybe because they were somewhere between an organ, string machine and synthesizer and didn't know who to appeal to.

By 1977, both the Moog Polymoog and the Yamaha GX-1 had been around for a couple of years and had introduced the world to the awesomeness of polyphonic synthesizers, along with some problems. The GX-1 was huge, expensive and relatively fragile. The Polymoog was plagued with reliability issues and was more organ than synthesizer. Coming from another direction, Oberheim had been quite successful in combining multiples of their SEM monosynth modules into two and four-voice polyphonic synthesizers. But there was a sense that convenient, reliable, and manageable polyphonic synthesis was just about to be willed into existence.

Out of the tension around the development of the perfect polyphonic synthesizer, and a full year before Sequential Circuits announces the Prophet-5, two extraordinary machines give it a go: the Yamaha CS-80, which is a story for another time, and the Korg PS-3300.

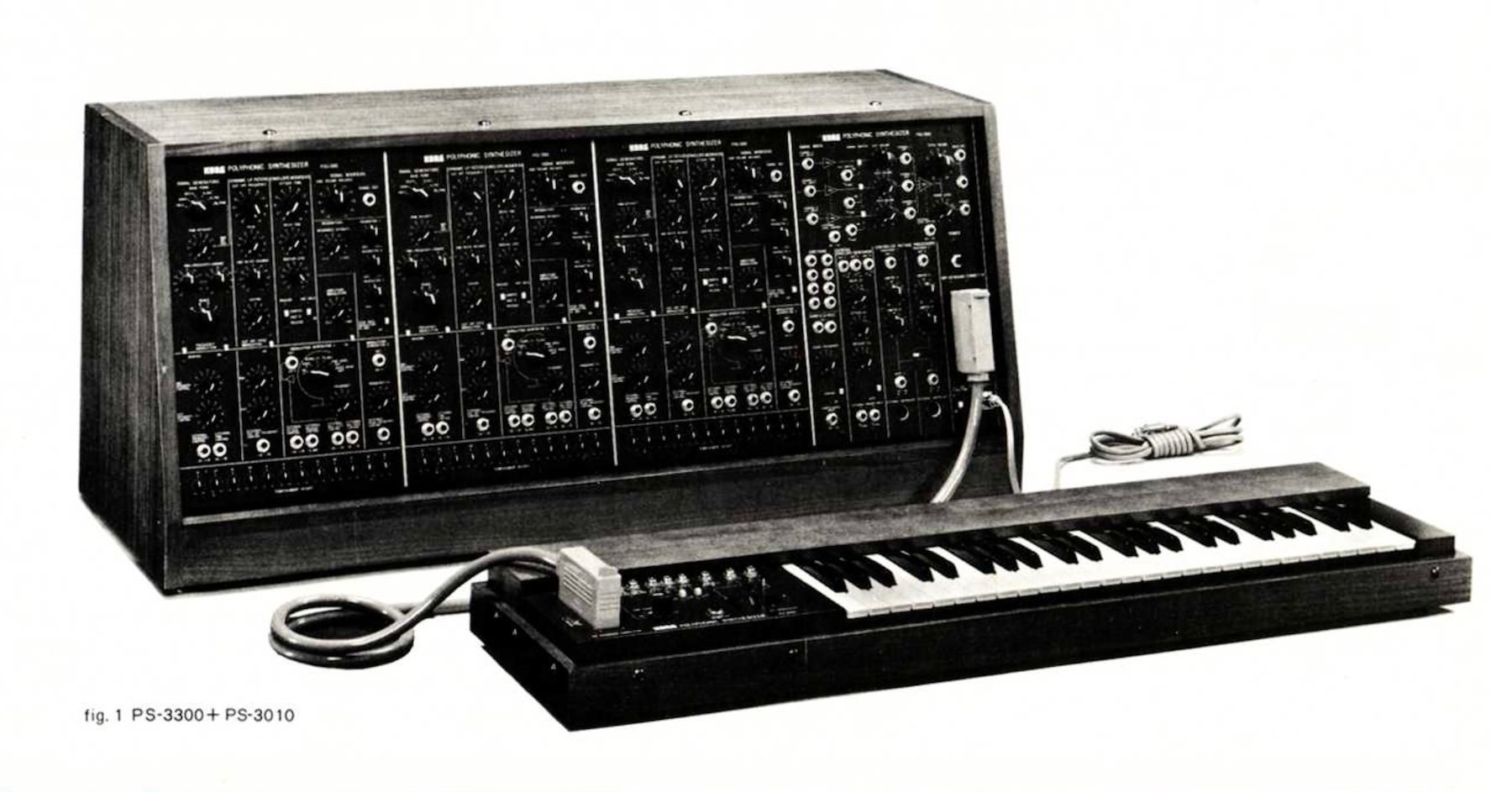

The PS-3300 and its smaller sibling, the PS-3100, were like nothing Korg had done before. The appearance seems to reflect elements of the Moog Modular, ARP 2600 and Roland System 700; it was all wooden cabinets, plug-in keyboard, knobs and patch sockets. It seemed like while everyone else was pushing for something completely different, Korg stepped in to take a snapshot of what a synthesizer could be if you packed in everything we'd learned so far. It was gloriously unfashionable, and at the time, the industry regarded it as everything they were gravitating away from. However, the technology, the polyphony and the pure synthiness of it were unparalleled. Let's have a closer look.

PS-3100

My first impression of the PS-3100 was how much it looked like the Korg MS-20, which came directly from it a year later. The PS-3100 is a fully polyphonic analog synthesizer. Mieda returned to the divide-down polyphony method of his prototype, using twelve oscillators to derive all 48 notes. Those twelve oscillators had independent tuning controls, so you could tweak them into something other than equal temperament. Maybe you wanted to tune to harmonics or use mean-tone or just-intonation; you could do that pretty uniquely on the PS-3100.

To fully articulate every note, they had to incorporate a filter, VCA and envelope with each divided-down oscillator. So that's 48 filters, 48 VCAs and 48 envelopes stashed inside the box. This had only really been possible since the Polymoog with the introduction of integrated circuits that built some of the synthesizer elements into chips rather than fleshing them out with individual discrete components. That said, in these evolutionary times, the PS-3100 was packed full of discrete components. To relieve some of the tension Korg reduced the discrete filter circuit down to the Korg 35 integrated circuit which ultimately ended up defining the sound of the MS-20.

The front panel followed a Minimoog style with separate, modular-like sections outlined with white lines and encased in a wooden console-style cabinet with a built-in keyboard. The temperament adjustment knobs for the 12 oscillators was stacked on the left-hand side. The oscillator controls were combined into the Signal Generators panel and offered a triangle, sawtooth, square, two fixed pulse waves and one with pulse width modulation. It had coarse and fine-tuning, an octave knob and frequency modulation fed in from the first Modulation Generator (MG1), or LFO as we'd call it, from an external source or the General Envelope Generator (GEG). An orange switch broke the line between the oscillator section and the modulator below it, turning it on or off, along with a switch to reverse the LFO. I really like the design of that switch dynamic.

For the lowpass filter section, we have Cutoff and Peak (or resonance) knobs, and a nice orange switch comes into play to activate LFO modulation to the frequency. There's also keyboard tracking and a knob labelled "Expand", which brings the envelope in either positively or inverted to play with the filter cutoff. The modulation options also let you use the GEG rather than the dedicated envelope or an external source.

Next is the Envelope section with Attack and Decay times, a Sustain level and then a Release switch with three settings. You can have it snappily short, half a second or so or "Long", which sets it to the Decay time. There's also an option for the keyboard to hold notes open. I'm told that the PS-3100 had a ridiculously long maximum Attack time of around 2 minutes—a feature that was not carried over to the later PS-3200.

Then we have an unusual bank of Resonators. These are three identical bandpass filters with separate frequency knobs, a common resonance control, and an overall cutoff controlled by Modular Generator 2. Each filter can range between 100Hz and 10kHz, giving you a wide scope for sonic manipulation. Adding the LFO gives it a real sense of flanging and sweeping, unlike any other synthesizer of the time. Under the Resonators is a Sample & Hold circuit for those fun bits of chaos and voltage sampling. It has its own clock or can be synced to the main clock. This has no normalled connections and can only be patched in via the patch bay.

Onto the modulation section, we have these two Modulation Generators and a General Envelope Generator. MG1 has a range of waveforms including pink and white noise, whereas MG2 is just a triangle. MG1 also ties into the Amplitude Modulator, which has an Ensemble effect before reaching the VCAs that are controlled by the GEG. The GEG has a number of trigger options, a delay amount and then just Attack and Release to shape the overall sound of the synth.

Throughout, the PS-3100 is semi-modular, so everything works as you'd imagine any synthesizer would. But on the right is a large patch bay where you can reconfigure the heck out of this synthesizer. As a patchable polyphonic synthesizer it was completely unique and landed almost at the exact time patch cables went thoroughly out of fashion.

The PS-3100 was a fascinating synthesizer that despite only being able to conjure up one oscillator per note, had a remarkable weight and warmth to it. The versatility was quite stunning in an environment where everyone else was trying to simplify their machines to make polyphony easier to cope with. But wait until you get a load of the PS-3300.

PS-3300

The PS-3300 is the voice and modulation section of three PS-3100s stacked into a single box, along with a mixer, a more localized patching system, utilities and an optional keyboard. This means it sounds three oscillators per note, giving it a richer, thicker, and more satisfying sound.

[Above: Korg PS-3300 with PS-3010 keyboard, from the PS-3300 user manual.]

The voice sections are called PSU-3301 units, and it's all there, including the two Modulation Generators and Amplitude Modulation, but excluding the Sample & Hold that stayed with the General Envelope Generator in the right-hand PSU-3302 panel. Each 3301 unit was an independent polyphonic synthesizer so you could have all three on one note tuned, tweaked, modulated and sculpted differently. That's a huge scope for difference over 48 notes. The optional but essential PS-3010 keyboard also brought some additional features, including a joystick for expressive changes and different sorts of trigger modes.

It had an extraordinary capacity for huge washes of modulated sound. You can imagine the frustration and confusion at Moog as they were agonizing over what direction to take their troubled Polymoog. On the one hand, you had the charm of the Oberheim Eight-Voice being an old-school massive synthesizer where each voice was an individually programmable synth, and on the other, the elegance and sophistication of the futuristic Yamaha CS-80 with its innovative voice cards, performance controls and contained front panel. In the middle was this folly of an extraordinary polyphonic synthesizer that was swimming against the tide and very likely to drown under the inertia of progress.

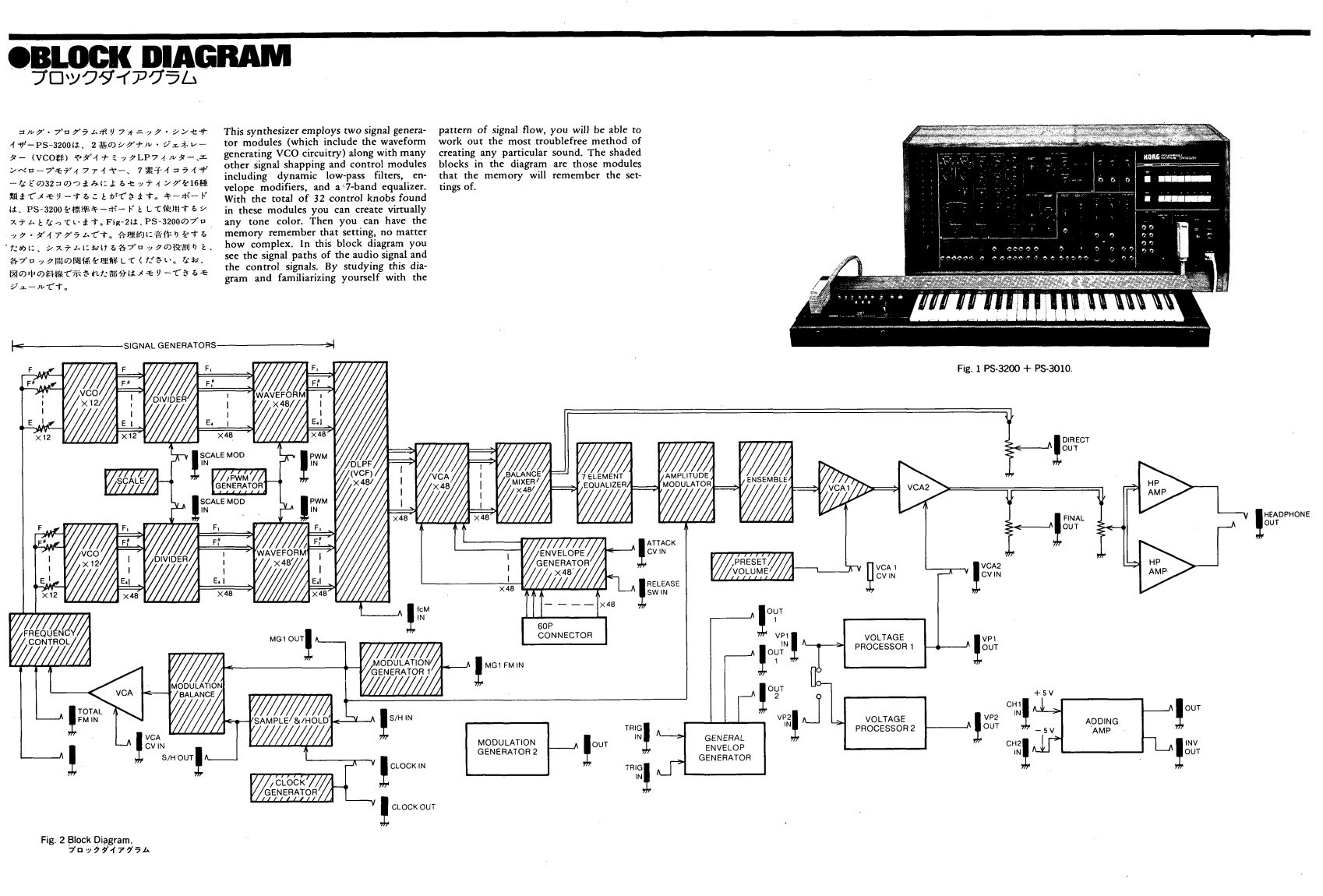

PS-3200

However, just before the Sequential Circuits Prophet-5 sealed its fate in 1978, Korg released the PS-3200, which attempted to find a middle way.

Costs were reduced by dropping to only two PS-3100 voice systems combined into a more coherent two-oscillator form, with combined filters, modulation and envelopes under a shared front panel. A much less impressive EQ replaced the Resonators, and the future was grappled with by building in a 16-slot programmer for saving patch configurations. However, the Prophet-5 was sleeker, smarter, could record every knob and had more space to do it. In comparison, the PS-3200 was an unfashionable hunk of junk that was of little interest to the emerging New Wave artists who wanted nothing to do with its prog-rock aesthetic.

Overall, only a few hundred were ever made. It was the perfect synthesizer for a moment within a turbulent time of extreme change and development. Its rarity is one of the reasons why Korg has decided to resurrect it for a limited time, in very limited numbers, at a very premium price.

PS-3300FS Reissue

Korg says the newly-announced PS-3300 FS is an opportunity for them to re-discover the processes and initiative it took to build such a synthesizer. They relish the chance to relive a very particular time in synthesizer history when everything was becoming possible. A few little tweaks have been made to the envelopes: the keyboard now has 49 notes, the programmer has been ported across from the PS-3200 and given 16 banks of 16 slots, and it's been fitted with MIDI and USB. The price is expected to be around $13,000.

I was fortunate enough to have a look at the prototype at the Korg Gallery exhibition in London. It's an impressive piece of work and gorgeous to post-modern eyes. It doesn't really need to exist—we would have all gone on none-the-wiser without the reissue, but I can see the value that Korg projects into it in terms of understanding analog circuits and how synthesis functions and comes together to produce something special. While few of us will end up owning one, I hope it will inspire young Korg engineers to swim against the tide and develop the next perfect synthesizer.