When it comes to cringe-worthy genre names, "Intelligent Dance Music" is a pretty tough one to beat. The inherent pretense and implications of such a moniker have meant that it has been routinely derided by both fans and artists alike—to the extent that, in one especially infamous quote, a notable producer (who shall remain nameless, since I was unable to find an authoritative source for this supposed utterance) reportedly stated that anybody associating their music with the hated term "should be shot." Extreme? Perhaps, but not an uncommon sentiment. Passions, they run high.

In all honesty, such fervent opinions on the definition of IDM, as well as the scope of its application initially made me wary of even addressing this topic. Do I really want to dive headfirst into this pit of snakes? Who am I to speak on such a thing? Am I ready for the derisory e-mails which will flood my inbox?

Never one to knowingly avoid a challenge though, I decided to risk the grumblings of Internet pedants, because whether people like it or not—IDM remains a term that is associated with particular characteristics of electronic music; characteristics that I happen to enjoy, and actually enjoyed long before I ever realised there was a name that encompassed them in some form or another. Whether or not IDM constitutes a "genre" as such that we can all agree on is ultimately irrelevant. IDM is a "thing," and a thing that is worth considering. So strap in.

Defining IDM

Recently, while boring one of my friends about this topic, she asked what I meant by IDM. The best explanation I could think of in response was "music that makes your mind go brrrr," which I actually think is pretty accurate. In fact, it’s not a million miles away from the genre’s alternative name, "braindance."

Attempting to come up with a definitive, detailed description of IDM would of course be a fool’s errand. However, I think it would be fair to say that there is a loose collection of common sonic characteristics that are generally indicative of whether or not a track could be considered as IDM. These may not be as tightly prescribed as other genres, but they do still exist. I dare say that in some ways, IDM can probably be considered in a similar fashion to other broad musical sub-categories like "alternative rock." Not every associated act will fall perfectly under that umbrella, and there will of course be specific pockets within the greater whole which might not have much in common with the others, but a shared thread exists nonetheless.

Generally speaking, IDM can (in my humble opinion) be categorized as a kind of electronic music which makes particular use of experimental or textural elements. In other words, deeper layers than you might expect from traditional electronic dance music. This may include broken, glitched, or otherwise heavily processed beats, sometimes set against undulating ambient melodies that dissolve, fracture, or do unpredictable things over time. There are commonly liberal helpings of polyrhythms and complex arrangements, but that isn’t a necessity. Plenty of IDM does have a straightforward core, with intricate edges that blossom out in many different directions…but we’re talking about the kind of stuff that plays with your ears and tickles your brain, especially if you happen to have imbibed in some kind of psychedelic substances. IDM isn’t (or at least, shouldn’t be) formulaic. This isn’t painting by numbers. It is authentic, exploratory, and compelling.

History

As the story goes, the genesis of IDM as we know it originated with a compilation series from legendary independent British label Warp Records. Beginning with Artificial Intelligence in 1992, this included early tracks from the likes of Autechre, Musicology, and Aphex Twin—even if they weren’t using those names at the time. American enthusiasts set up a mailing list inspired by this, named "Intelligent Dance Music"—a term that stuck, much to the chagrin of those over the pond—and in spite of attempts by Warp to avoid that happening with an explanatory note included alongside the release of Artificial Intelligence II in 1994.

Whatever the origin of the term itself, prior to IDM’s emergence, popular electronic music was often heavily focussed on its suitability for the dancefloor. In other words, what will get people moving and keep them there. In contrast, IDM has regularly been described as designed or intended for "home listening," where the layers of sonic experimentation can be more readily noticed and appreciated, without the pressure of having to sustain a rhythm that encourages physical movement. That’s not to say that you can’t dance to IDM…you most definitely can (though maybe not "Cbat"...). It’s just that this wasn’t necessarily its primary function.

What sounds excellent in a club environment with a massive sound system can easily sound dull or lifeless in isolation. This idea that composition and stylistic choices are guided by the venue in which a listener is going to experience music is not a new or novel one, and something that David Byrne of Talking Heads fame talks about in his book How Music Works—which is well worth a read. Whether or not artists set out deliberately to create music for people to sit and listen to on their headphones or not is kind of irrelevant though. Ultimately, as a description it helps to provide a way to help understand how the sonic palette may naturally have developed over time through experimentation and divergence from norms.

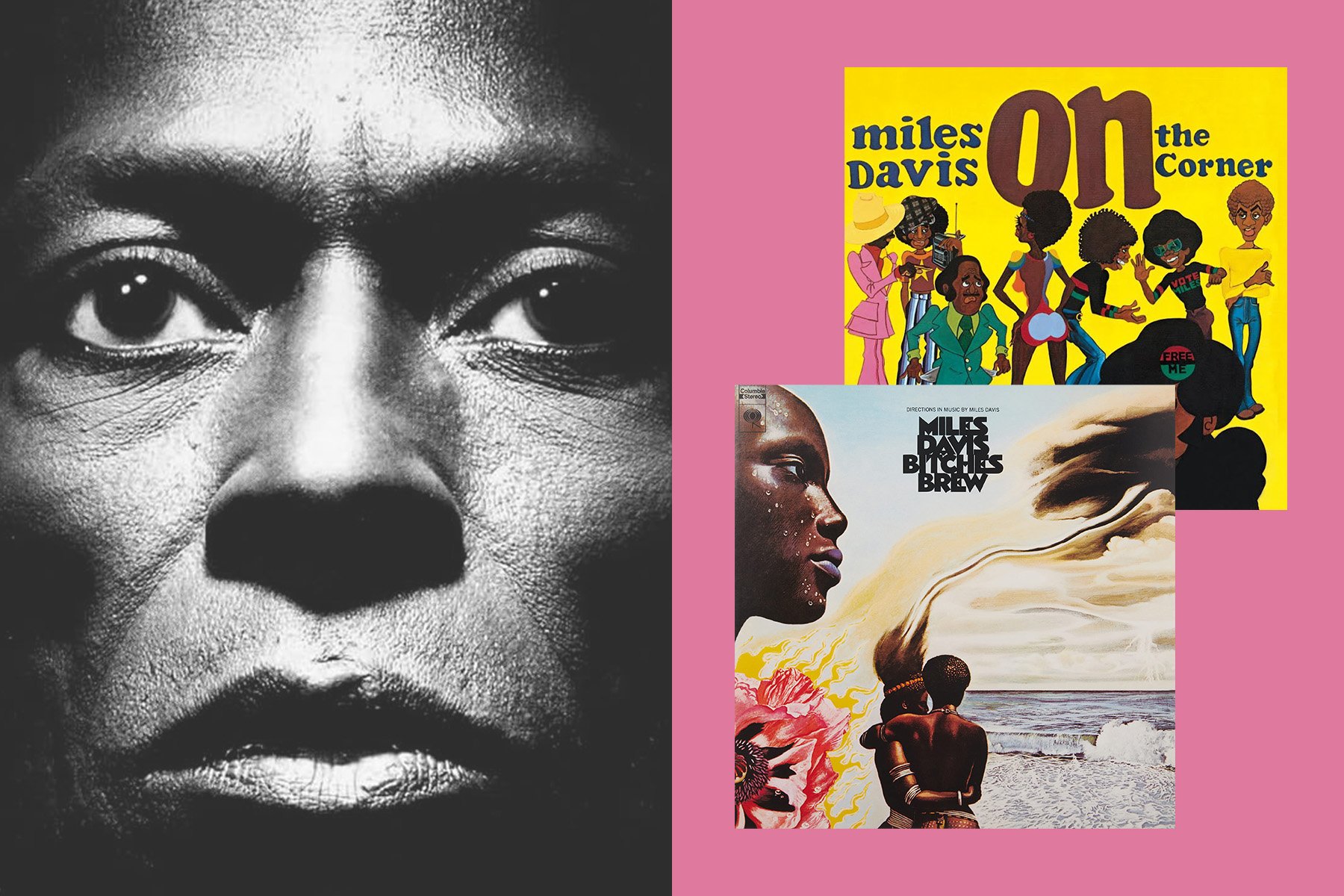

With this in mind, IDM shouldn’t be viewed simply as a complicated offshoot of or reaction to EDM. Instead, its origins are deeply rooted in and remain associated with other deeply creative genres such as hip hop and techno. These influences are clear throughout its lineage, and there is significant overlap and commonality with the practices and philosophies of wider sampling culture—including breakbeat and jungle. You don’t have to jump too far to get from Hudson Mohawke to J Dilla, which is partly what makes it such a rich and compelling world to get lost in.

The Gear

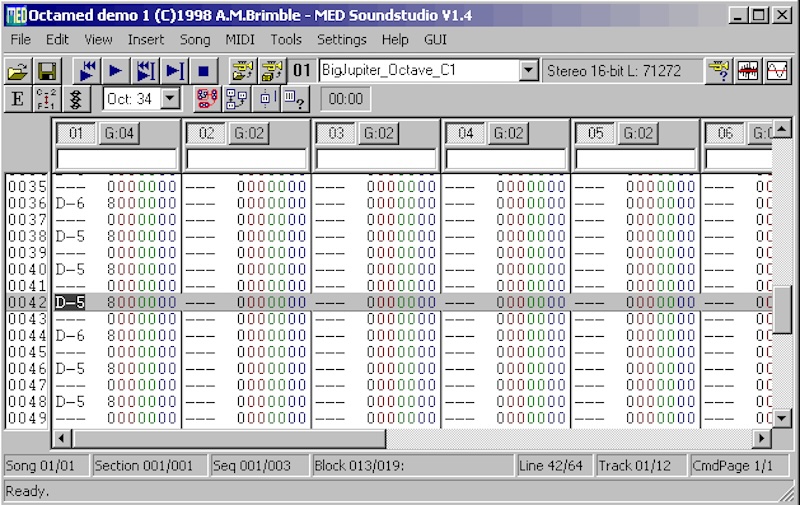

So let’s talk about the gear. Many of the most distinctive sounds from IDM were made possible by the emergence of technology in the late '80s and '90s which allowed producers to chop up and play around with audio in ways that were never possible previously. Use of samplers like the MPC series, and tracker software like OctaMED on the Amiga were particularly popular for this, and in addition, the unashamedly digital effects of the era lent colour to the more ambient elements, with the Alesis Quadraverb rack unit remaining sought after to this day, thanks to its ability to simultaneously apply and control four different types of FX at once over MIDI.

In some ways, trying to emulate the stylistic choices of legendary IDM producers would seem to go against the genre’s underlying philosophy (if there is such a thing). However, that doesn’t mean that you can’t be inspired by their approach or techniques. There are now a plethora of tools available that make bending and manipulating audio easier than ever before, to experiment in the spirit of IDM. Grooveboxes that allow for the modulation of different parameters on a per-step or sub-step basis are particularly suited for glitching up or re-arranging elements of a composition in pleasing ways. Elektron’s parameter lock functionality, employed in devices like the Digitakt and Octatrack lend themselves nicely to such a task. Both the Polyend Play and Tracker are also especially good at producing variations, especially with their creative performance modes that allow you to flip and stutter sequences on the fly. The Play even includes pre-set IDM pattern generations… though whether that’s a bridge too far or not is something that you’ll need to decide for yourself.

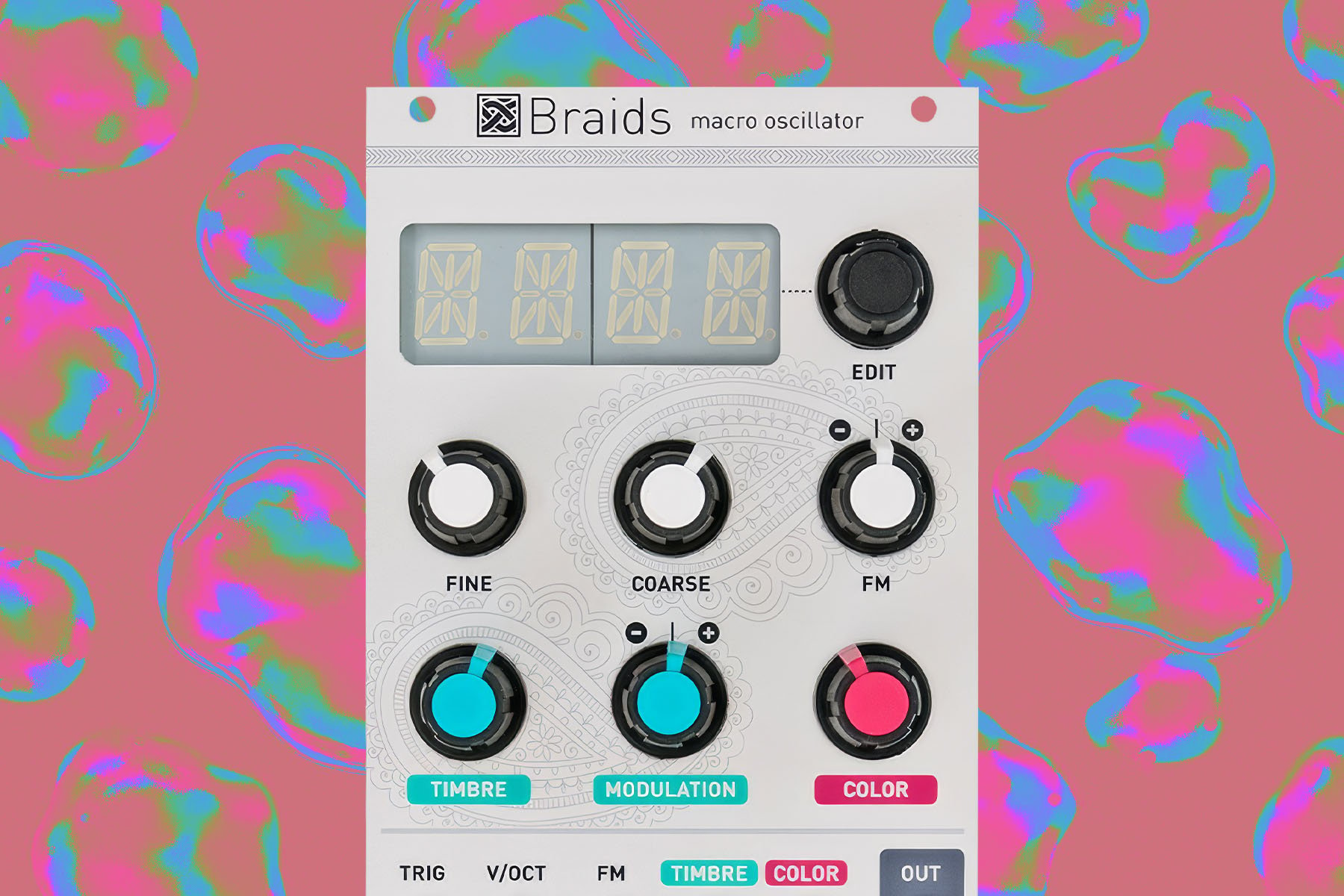

Of course, Eurorack inevitably provides some of the most interesting possibilities for processing and mangling audio. One of my personal favorite modules for this kind of task is the Qu-Bit Data Bender, a stereo "circuit bent" FX module that will chop up, "skip," and generally just obliterate whatever signal you feed into it—with gloriously trippy results. Similarly, Intellijel’s Rainmaker is a glorious multi-tap delay which has a mind boggling array of features to drip and cascade sounds across the stereo field, taking it well beyond the realms of what you might expect such a thing to be capable of. Quadraverb, eat yer heart out. For those crunchy textural sounds, Akemie’s Taiko is an excellent choice. Described as an "FM Drum Voice," it is so much more than that. So much more. Ear candy, galore.

Assorted Listening

When it comes to examples of IDM, there are of course many genre defining classics from the big names in the 90s, but there are also incredible gems from more contemporary producers as well. Here is a personal selection of some of my own highlights, which have been hand-picked deliberately with that in mind. I will of course have missed many essentials, but I only have so much space, so accept my apologies in advance.

Artificial Intelligence - Warp Compilation (1992): It would seem to make sense to specifically mention the LP that is credited with the genre its name—though this is far from a token inclusion. The 10 tracks exhibit clear diversity, while also retaining a common thread, something which can help illustrate some of the defining characteristics of the genre. Listen out for the tempo shift at 3:27 in "Crystel." Oft.

Aphex Twin - Windowlicker (1999): Aphex Twin is so indelibly linked with the lore and history of IDM, and has produced so many great albums that it would be impossible to pick just one, and so in what is perhaps something of a cop-out, I am going to recommend just one track: "Windowlicker."

To some this might seem like an uninspired choice, given the track’s popularity—but I actually think that is what makes it such a great example. Perhaps more than any other track, this is one that folks might already be familiar with: the kind of "song" that enters the mainstream consciousness and changes the way that people think about electronic music, shattering preconceptions. Even now, when I hear the distinctive sounds of this 1999 release, it still makes me think: “What is that, and how can I get more of it?” It’s indescribable, and brilliant. If you do want more, then I’d recommend the earlier Richard D. James album from 1996. Or perhaps listen to the White Lotus theme song (don’t try tell me this wasn’t an inspiration for Cristobal Tapia de Veer).

Mouse on Mars - Autoditacker (1997): Each track on this album has its own distinct, playful personality. From the start, with "Sui Shop," I love the slidey synths, the boings, and the sucky sucky sucky sucky noises that appear from the outset (go on then, you listen and see if you can do better).

Boards of Canada - Music Has the Right to Children (1998): For the longest time, I was indifferent about the existence of Boards of Canada. That is probably because I thought I knew what they sounded like, but I was wrong. Their inclusion here is definitely not just nepotism for my fellow Scots either. This album is regularly touted as one of the best examples of IDM that you can find, and tracks like "An Eagle in your Mind" demonstrate why—the use of stereo panning flipping my brain into an altogether different state every time.

Telefon Tel Aviv - Fahrenheit Fair Enough (2001): By the time the blips and clicks and trills that are spread across the stereo field kick in on the title track of this album at the 2 minute mark, it almost feels like too much; as if you are stepping into a forest filled with dense swarms of fast-moving crickets. But…if you are in the right head-space, the juxtaposition with the ambient instrumentation is both stimulating, yet calm and sublime all at once.

Wagon Christ - Musipal (2001): Wagon Christ is one of the many names under which acid aficionado Luke Vibert has released his creations. This release effortlessly blends elements of hip hop, breakbeat, acid, and a host of other styles in a gorgeous melting pot.

Prefuse 73 - One Word Extinguisher (2003): This is an album that traverses a lot of stylistic ground, from hip hop (on tracks like "Plastic") to lo-fi, and even chiptune at times ("Choking You"). It does so without it ever sounding un-natural or contrived, and while it might not be immediately obvious, it displays a lot of the hallmarks of IDM—as well as its inherent relationship with beat making culture. Listen, and you’ll see what I mean.

Four Tet - Rounds (2003): The first (and only) time I have seen Four Tet was back in 2007, at Glasgow’s legendary Arches venue (RIP). Rather than the usual mass of gyrating bodies, I instead vividly remember seeing him surrounded by open-mouthed revellers, nodding their heads in awe—more interested in what he was doing than dancing. It is entirely possible (probable, even) that I’ve imagined this whole thing, but it makes a lot of sense in the IDM context. Revisiting this album recently to write this piece was a delight—a beautiful blend of acoustic and digital that feels entirely organic.

Max Cooper - Yearning for the Infinite (2019): Proving that IDM still has its place to this day, Max creates the most beautiful ambient soundscapes which pulse and breathe, scratching an itch that you didn’t even realise you had. "Perpetual Motion" offsets beautifully evolving chords which feel simultaneously hopeful and melancholic, interspersed with ratchets, snaps, and other digital distortions to open up your third eye.

Conclusions

I don’t claim to be any kind of expert in IDM, or really to understand it—if such a thing is possible. However, as a genre, it definitely sits at the outsider, more idiosyncratic edge of electronic music, which is exactly where I feel most at home.

There are of course IDM purists who will claim that the label only truly describes a number of specific early acts that were associated with Warp Records, much like how "real" punk is limited to specific acts from a particular part of England in 1979. However, I don’t really accept that. One of the original reasons that IDM developed as a term in the first place was to encapsulate the type of music that people were making, but which didn’t have a home anywhere else…relegated instead to the B sides of harder, more straightforward dance music. As music production technology has become increasingly more accessible, and the number of bedroom producers exponentially increased, there is surely more of a place for IDM than ever before. Those who allow themselves to see past the terrible name will be rewarded.