When an artist lives fervently, it is hard for their story to not be remembered. So is the case for German engineer, inventor, poet, musician, and philosopher Harald Bode—one of the patron saints of electronic music. Bode was a visionary engineer who saw the promise of the modern circuit and helped realize the dream of synthesis. Born in 1909 in Hamburg, Germany, Bode invented over 50 musical instruments and holds over 20 patents in the United States, Canada, and Europe.

Bode is well-known for presenting one of the earliest modular synthesizers in the early 1960s—before Moog and Buchla had assembled their first voltage-controlled instruments. Bode's name should also be familiar from the legendary Bode Frequency Shifter, which can be heard on groundbreaking works by composers like Wendy Carlos and in the pop sounds of Kraftwerk.

His vocoder, the Bode Vocoder, even made it onto the David Letterman Show, controlled by "diva of the diode" Suzanne Ciani, who also used the vocoder while doing sound design for the Bally pinball game Xenon and on the uncanny, disco rendition of Star Wars themes, Star Wars and Other Galactic Funk, released in 1977 by Meco.

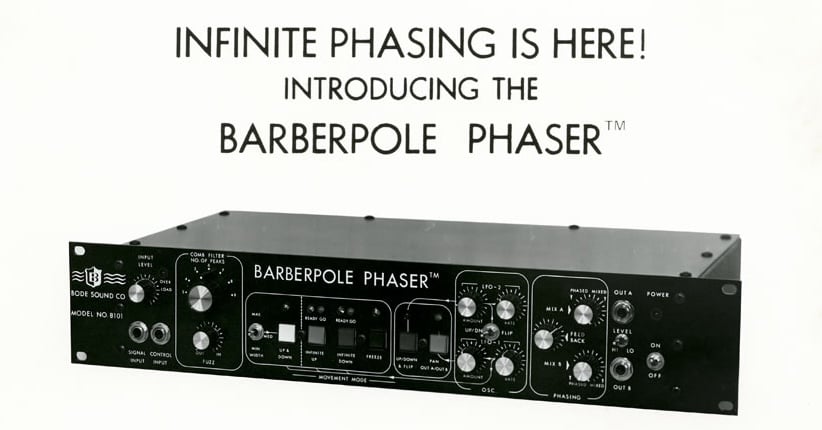

Even one of Bode's more enigmatic-but-futuristic instruments, the Barberpole Phaser—which is based on the “Shepard scale and the Shepard-Risset glissando,” and applies “an everlasting glissando upwards or downwards, as long as the tone is played"—stands alone as a wholly unique and unmatched device. The phaser, whose use was sparse after limited release at the end of Bode’s career in 1981, is capable of complex harmonic processing, making it a powerful tool, even by today’s standards.

Bode was a devout archivist whose journals and schematics bordered on poetry—full of narrative and precise, evocative illustrations. Through his journals, his collection of patents, and collaborations, he made it a point to share his knowledge and vision with all who could benefit. Bode worked closely with Dr. Robert A. Moog and lent his hand and design to the Model 1630 Bode Frequency Shifter and the Moog Vocoder. His openness to cooperation would be a defining feature of Bode’s prolific career.

Harald Bode’s story, however, starts well before the synthesizer and these experimental audio electronics. His lofty ideas about technology, the human spirit, and creativity would change the trajectory of musical expression and instrument design—and offer an illuminated path toward the future of sound.

A Spark to Start

Harald Bode’s career spanned almost 50 years, beginning in 1935 when Bode started to work in the field of electronic instruments.

Always a musician, Bode learned to play the organ from his father, who was a pipe organist, and his mother, who played the harpsichord; and he always brought a sense of creative wonder and affinity to sound that only an artist could understand. His journey began with a crossover of technology and sound when he started a home recording studio at the age of 26.

Orphaned at the age of 18, Bode’s love of music and musical expression carried over from his parents and lived exponentially through him—and it cannot be understated how much music was around him throughout his life. Fresh out of Hamburg University after studying physics, mathematics, and natural philosophy, Bode would put his degree and genius in physics and philosophical curiosity together to apply it to his true drive: music.

Looking back, an older Bode said in 1979, “I had always the desire to create the means to express myself in a new way (musically)… to bring about sounds, which I visualized… sounds which I thought would be possible.”

And as a young technologist, Harald Bode’s home studio would be the patch from which his practice would grow. Bode’s studio featured an unpatented Steinway-Hiller Grand Piano, in which pickups were used to amplify the piano’s string vibrations for recording. Bode was able to modify the piano to his own liking, a task which spurred him to imagine creating an electronic instrument all his own, one that would generate sound from electronics not acoustic techniques.

A First Offering

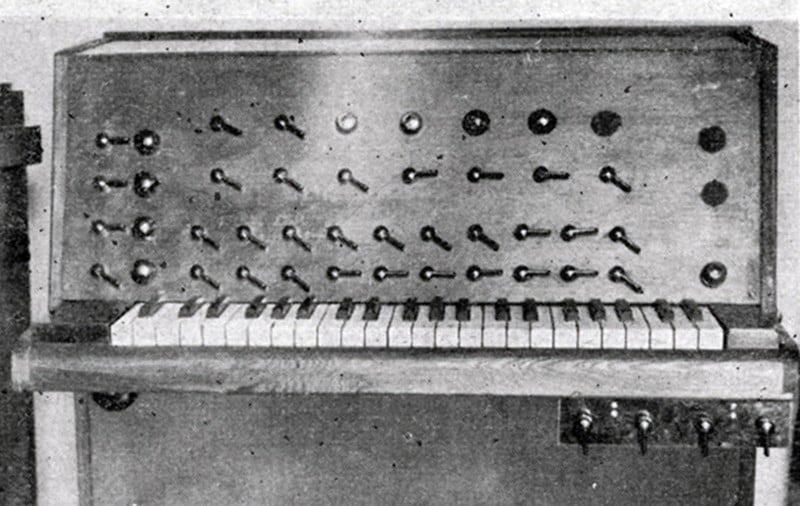

Bode would push the work of his predecessors like Dr. Frederich Trautwein’s Trautonium and physics concepts like Hermann von Helmholtz’s theory presented in On the Sensations of Tone as a Physiological Basis for the Theory of Music to a new limit with the invention of his first electronic instrument—the “Warbo-Formant Orgel”, also known as the Warbo-Formant Organ.

First presented in 1937, this instrument would be Bode’s first novel contribution to the music world, boasting a unique electronic design that presaged today’s modern synthesizer. The Warbo-Formant Organ featured four oscillators and allowed the user to achieve partial polyphony, which was revolutionary for the time. The oscillators themselves were “relaxation oscillators”, a type of voltage controlled oscillator (VCO) circuit that generates a non-sinusoidal output signal—a square or a triangle wave, for example.

Bode explained the sonic qualities of the Warbo as such:

"It had two sets of filters and a four-voice assignment keyboard through which, for instance, voices 1 and 3 could be assigned to the first filter and voices 2 and 4 to the second filter. By making the pass regions of the filters mutually exclusive, complementary tone colors could be produced, which sounded very pleasing to the ear."

Historically speaking, Bode's first-hand account is invaluable—as no copy of the Warbo exists, and there are no known recordings of the instrument that survive to this day.

A huge step from Thaddeus Cahill’s 1896 Telharmonium, which was massive in comparison and used giant dynamos to synthesize sine waves of pure sound, the Warbo featured a similar groundbreaking quality—in this case both precise engineering and perfected expression capabilities. Made possible by the patronage of composer and bandleader Christian Warnke, the name is an amalgamation of the pair’s last names—WAR and BO.

Notably, the Warbo was perhaps the first electronic instrument to feature polyphonic voice assignment technology. The first of many limited-polyphony synthesizers, the Warbo utilizes Bode's own assignment system to solve the problem of having more keys than sound generators—in this case, four sound generators for the instrument's entire keyboard. These systems can be as simple as a “time priority” rule, where voice one is assigned to the first key pressed, voice two to the second, and so forth. Electronic instrument designer, historian, and Moog legend, Tom Rhea covered the Warbo in his Contemporary Keyboard column “Electronic Perspectives”, recently released as a book, and describes the Warbo assignment system, which is based on “high key priority”:

Bode would leverage this new trajectory with the Warbo in 1938 when he brought the instruments to the Heinrich Hertz Institute for Vibration Research at the Technical University of Berlin, famously where Fritz Sennheiser, founder of the company with the same name, once taught.

Hitting the Ground Running

During his post-graduate studies in Berlin, Bode collaborated with high-frequency physicist and electroacoustic instrument designer Oskar Vierling and musician Fekko von Ompteda to further expand his vision for sound and instrument design. While at the Heinrich Hertz Institute, Bode enlisted Vierling to help him realize his next instrument: the Melodium.

The Melodium was a monophonic, touch-sensitive synthesizer which presented solutions to some of the trouble points of the Warbo organ. Unlike the Warbo, which had limited polyphony thanks to four oscillators, the Melodium took advantage of one of the more forgiving features of a monophonic instrument—it is easier to tune. On top of The Melodium’s more streamlined tuning, its touch-sensitive control let the user access the ground-breaking expressive control of timbre via a method that resembled the known piano keyboard. The Melodium was heard throughout Germany in state film, one of Germany’s first television stations, and opera.

Bode's Melochord

Bode's Melochord

Both the Warbo Formant Organ and the Melodium would be destroyed in World War II, though the design of the Melodium would be repurposed and refocused in Bode’s next instrument, the Melochord—perhaps the world’s first post-war electronic instrument, which was completed in 1948.

Bode would continue to release electronic instruments similar to the conventional, organ-format instruments for the next decade.

However, he would close out his career in Europe with totally different instruments—the Cembaphon, an electronic, amplified harpsichord, and three smaller stage keyboards—his own design for a Clavioline, built off a widely shared patent from instrument design Raymond Martin, to which Bode would add two additional octaves for even more sounds, as well as the Tuttivox, and the Combichord.

These instruments would be placed into a much more accessible market. At the time, organs had a more limited use, mainly cinema, TV, and radio, and were still considered culturally taboo, banned from churches in West Berlin and publicly ridiculed, one newspaper claiming "Bach can not be played with an electronic organ." Bode's new smaller, niche instruments were perfect for German dance and pop musicians. He would later design two more organs—but not in Europe.

A Bright Future

In 1954, Bode uprooted his family in Bavaria, Germany and moved them to Brattleboro, Vermont, USA. Accepting a job at the Estey Organ Company, Bode would leverage his international acclaim as the designer of the Melochord and some of the first mass-produced organs in Germany, to take the office of Vice-President and Director of Research and Development at the New England instrument maker.

Bode would design two organs at Estey: the Model S and the Model AS-1, which were advancements on the Bode Organ.

Since 1935, Bode had taken great steps to create instruments that created new sounds, in new ways, for new audiences. His work with VCOs and beautiful circuit-based sound colors always pushed up against what organs and keyboards were at the time.

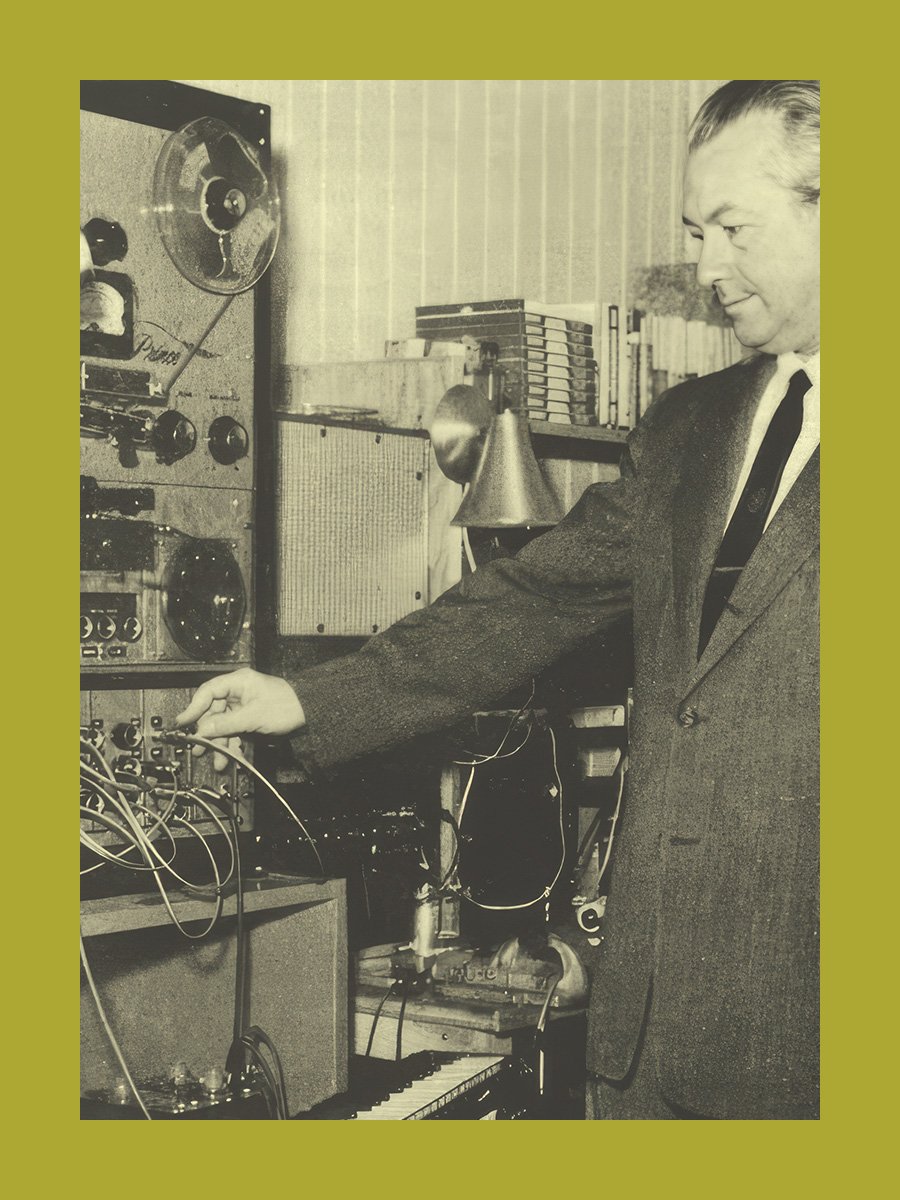

But it was not until 1960, when the Estey Organ Company closed its doors, that Bode would have the focus needed to fully launch his newest instrument, the Audio System Synthesizer, the framework from which the modern synthesizer was formed and the direct predecessor to the giants of original synths, Moog and Buchla.

Home is Where

In 1959, Bode would set up the hub in which some of his most fantastic ideas would develop: the workshop from which his next three of instruments would emerge, in the basement of his family’s home. His basement workshop is truly a special place—Bode would conduct business, design, do interviews, and perform with his instruments all within the tiny space.

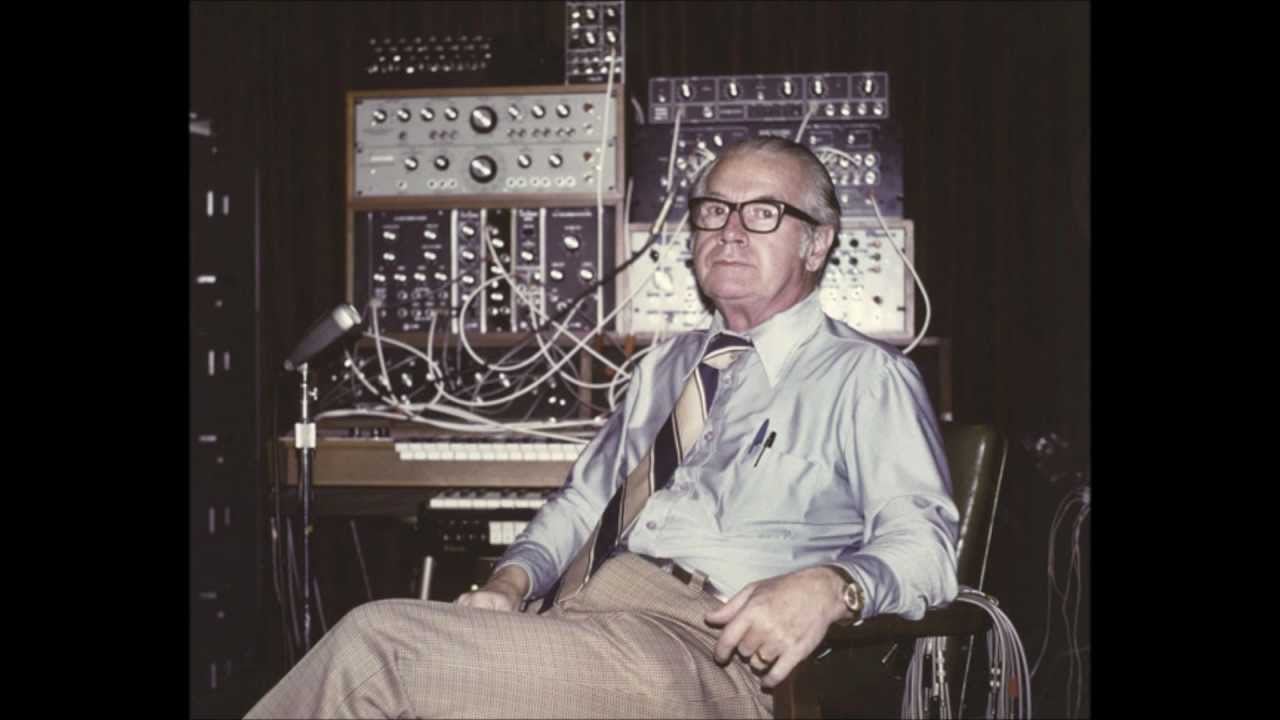

Harald Bode with his Audio System Synthesizer

Harald Bode with his Audio System Synthesizer

His son, Peer Bode (artist, educator, imagination advocate, and member of the legendary sound project Carrier Band, along with legends Pauline Oliveros and Andrew Duetsch), remembers the house vibes fondly: “I grew up hearing rich, big sounds.”

Bode, who often worked alongside his wife, would spend much of his time designing instruments and tools, but also playing his instruments—and according to Peer, he liked to play often, and he always played with the volume way up. Bode’s son describes sound floating up from the floorboards, filling the space.

It was important to Bode that there be no difference between creation of beauty in sound, and in design: “It is a constant evolutionary thing… not for the sake of filling up this room…making it more sophisticated…but for the sake of having new and more ways for limitless expression.”

One of Bode’s personal philosophies, perhaps adopted during his studies with Ernst Cassirer in Hamburg back in the 1930s, was to cultivate many talents and to constantly grow them. Perfectly imaginative and curious, this sort of thinking was all throughout his journals: through different narrative forms (poetry and memoir) and unique and exact illustrations, his multiple interests and talents can be easily observed.

It was exactly Bode’s ever-evolving vision and relentless curiosity which helped bring about the Audio System Synthesizer.

Connecting the Modular Dots

The Audio System Synthesizer is arguably the first modular, voltage-controlled synthesizer ever created. This method of sound creation is the exact basis for the better-known Moog synthesizer and the first Buchla systems—we can see this concept everywhere today, as modular synthesizers and Eurorack-format audio electronics are more popular than ever.

The concept may seem straightforward: a modular device to comprised of multiple components, all of which can be connected when necessary, adding or modifying sound colors immediately, as the user designs them. The execution was revolutionary; it was designed to be so usable that its technical complexities would be completely transcended by its immediacy and performability.

Bode presented his new synthesizer to the world at the 12th annual Audio Engineering Society convention in the fall of 1960; a treatise describing the modular system was then published in the Journal of the Audio Engineering Society a year later in 1961, effectively predicting that test-equipment-based electronic music studios would soon evolve into more accessible, portable, and even affordable ways for musicians to design totally new sounds.

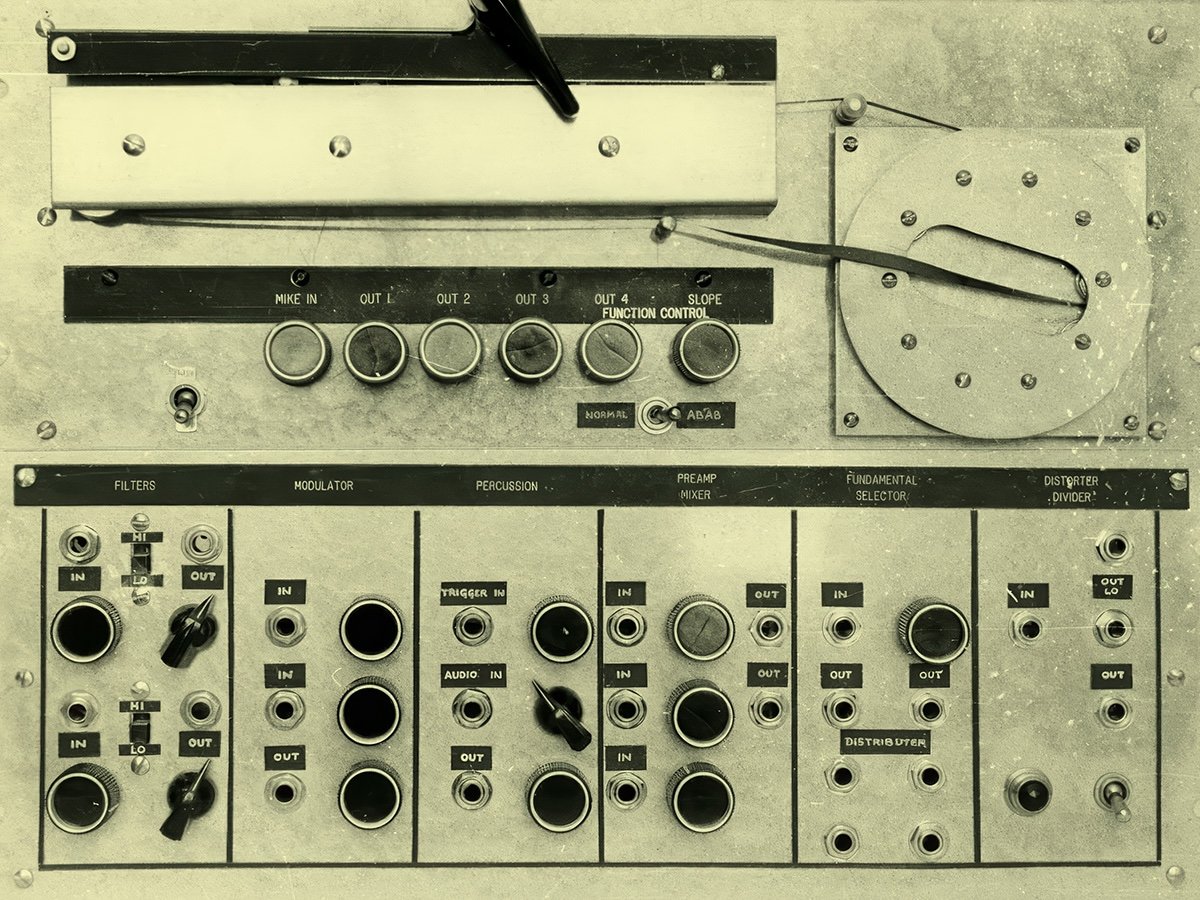

Bode described the specifications of his modular synthesizer as such in his essay “A New Tool for the Exploration of Unknown Electronic Music Instrument Performances”:

“1. dual channel filter, each channel comprising a low pass, a high pass, a tunable formant filter and a mixer capable of blending the low pass or high pass with the formant filter performance; 2. A ring bridge modulator; 3. An audio controlled or triggered gate and percussion unit; 4. A fundamental frequency elector; 5. A squaring circuit; 6. A binary divider ; 7. A pre-amplifier ; 8. A mixer ; 9. A distributor; and 10. A tape loop repetition unit with several reproducing heads correlated to selective outputs and capable of creating rhythmic effects with alternating timbre patterns.”

The synthesizer was able to create an almost unlimited number of sounds through a novel use of envelope shaping, control voltage triggers, and tape looping. Each module featured two input jacks capable of receiving audio and program information. By amplifying audio up to the level of control voltages, the synthesizer allowed performers to use melodic, audio content and percussive, exact, and repeating program information to generate tones, shape envelopes and modify signals in any combination of ways—literally converting the world around the performer into life that pulsed through the machine.

All sounds were mixed out to an amplifier and the onboard tape recorder. The tape recorder could function as a “tape repetition unit” or looper with three playback heads, each with their own outputs, capable of adding their own respective tone colors and repetitive effects.

Bode’s modular synth would certainly crown his lifelong pursuit of merging science and symbolic forms, again using cutting-edge circuit design to embellish and more accurately capture the experience of life—he was a technologist, but he was always human.

Revolutionary Fixtures

Tom Rhea describes Bode's ability to manage the pragmatic brain and the creative brain—and never discriminated between the two. He was a fantastic salesman, but he was also a passionate musician. Some of his instruments found limited, sound design, sometimes avant-garde, uses, while others were intended for pop music.

Harald would work with Tom Rhea and Robert A. Moog while collaborating with Moog in the '70s. Moog would end up using many of Bode’s circuits. His design for a frequency shifter—a circuit which can take an audio signal and shift the entire frequency spectrum “accurately and continuously”—was capable of shifting the frequency plus and minus 5000Hz(!). This device was produced by Moog as the Moog 1630 Bode Frequency Shifter.

The performer could get amazingly colorful results by shifting the giant knob on the front panel. The instrument was used almost religiously by Kraftwerk, whom Bode loved and whose music he collected. You can hear the frequency shifter across the album Computer World, released in 1981.

In 1979, Bode and Moog would strike another victory with the Bode Vocoder 7702, affectionately known as the Moog Vocoder, based on the original Bode Vocoder, which Bode finished in 1975.

Up Until the End

Bode was able to design all of these instruments in his basement, the Hexenküche, or “witch kitchen”, under the banner of the Bode Sound Company, which would not only move units through Moog but also to studios like Motown, the Columbia/Princeton Electronic Music Studio, and Cologne Studios in Germany. From his basement, he would demo and record his instruments. Beautiful documents, the recordings represented his creative voice but also served a pedagogical purpose—giving a first-hand account of just what his instruments can do.

None of his instruments would need more explanation than his final piece of equipment, the fantastical Barberpole Phaser, based on a circuit which cleverly used phase blocks and envelopes to emulate the spirit of the Shepard tone and the Shepard-Risset glissando—albeit applied to a phasing process rather than pitch of generated tones. While the instrument was never produced extensively (only three models made), composers like Wendy Carlos saw its potential.

Bode would never stop working with others throughout his entire career. Carlos worked with Bode’s equipment while working with Moog, speaking further towards his ability to design instruments for use across the spectrum of popular music and avant-garde, experimental work. He would regularly share samples back and forth with Jean-Michel Jarre—he was truly a generous man passionate about music and the design and distribution of his amazing instruments.

Until his death in January 1987, Bode would never stop working to find new sounds and new ways of making them; toward the end of his life, he was even working on Commodore 64 programming.

Bode’s work ethic seemed to be unmatched, and his designs have had an amazing effect on popular culture all around the globe—it is unbelievable what we are capable of when we nurture our imagination and cultivate our skills with intention and joy.